The story behind the rhythm: Notes on a Brazilian love affair, Part 1: Samba

Nearly 15 years ago I was listening casually to the lovely songs on jazz singer Susannah McCorkle’s exquisite album Sabia in my car, when the song “Bridges (Travessia)” transfixed me. The nakedness of its emotions, the way its melody unfolded, its subtle rhythmic pull, and McCorkle’s acute delivery of its lyrics felt different from many of the American popular songs I adored. From studying the liner notes, I learned about its composer Milton Nascimento, which led me to pay more attention to other Brazilian musicians such as Antonio Carlos Jobim, Ivan Lins and Elis Regina. Soon, music originating from Brazil became an obsession.

I began my process by listening to some obvious Brazilian “classic” vocalists, like Astrud Gilberto (“The Girl from Ipanema”), and contemporary singers, like Bebel Gilberto and Celso Fonseca. Many of my favorite American vocalists recorded Brazilian Portuguese language songs in English, including Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, and Roseanna Vitro, which helped make the songs more accessible. Some of my favorite singers also recorded in Portuguese including McCorkle and Karrin Allyson. Listening opened my mind to delving more deeply into the history and context of the music. For example, I learned that the entrancingly melancholic harmonies and bittersweet lyrics I enjoyed in songs like “Bridges” and ballads like “Once I Loved” and “Meditation” exemplified the aesthetics of saudade. I also realized I was murky about the relationship between samba and bossa nova. Speaking with friends conversant in Portuguese and Brazilian culture, I learned that there were generations of post-60s and post-bossa nova Brazilian musicians ripe for discovery.

I willfully took the plunge and began reading more about the roots and evolution of Brazilian pop, which has helped me appreciate the music, the people, the culture and the country beyond the songs. In a sense, I feel like I am falling in love all over again. For U.S. listeners milestones like 1959’s Black Orpheus soundtrack, 1962’s Jazz Samba album, by Stan Getz and Charlie Byrd, and 1964’s iconic “The Girl from Ipanema” are key moments of exposure to Brazilian pop. However, the story goes back much further.

The Birth and Evolution of Samba

Brazil was under Portuguese rule until 1822. One of the key elements of West African culture that slaves maintained were Yoruba religious and spiritual traditions which morphed into the Candomblé religion in Brazil. 1871’s Rio Branca Law (Law of the Free Womb) aimed to protect the newborn children of slaves but was a stopgap measure until slavery was finally abolished in 1888. Many of those who were enslaved maintained some “Africanisms,” such as music, which led to indigenous song forms and styles like the lundu song form and circle dance, and later the maxixe which mixed lundu with elements of polka and Cuban habanera. Brazil’s first recording was a lundu based composition, 1902’s “Isto E Bom” (This is Good).

Many former slaves migrated from Bahia to Rio, especially the Praça Onze area. Neo-African cultural elements survived through female elders (“tias”) of these communities. The roots of samba grew out of a community of musicians who socialized at the home of Tia Ciata Ruo Visconde de Inhauma. The musicians who hung out were versed in multiple forms, including lundus, maxixes marchas, choros, and batuques, and ultimately shaped samba. 1917’s “Pelo Telefone (On the Telephone),” sung by Afro-Brazilian musician Donga, was the first officially registered samba composition. Sambas are highly percussive songs where handclapping or drums, and percussion (batucada) carry the main rhythm. Key characteristics of sambas were 2/4 meter with an emphasis on the second beat, a stanza and refrain structure, interlocked syncopated lines in melody and accompaniment, and a responsive interplay between percussion and voices. Two of the most important early samba composers were flutist and arranger Pixinguinha and pianist Sinhô known as the “King of Samba” in the 1920s.

Sheet music for 1917's "Pelo Telefone" sung by Donga.

In the Estácio neighborhood of Rio, near Praça Onze, a generation of composers (“sambistas”) emerged who expanded and refined the form experimenting with notes, tempo, harmony, and lyric possibilities. Musicians experimented via Escola de Sambas (“samba schools”) groups of musicians who were the equivalent of musicians’ clubs that composed songs for Brazil’s annual Carnaval celebration. The combination of compositions by composers like Ismael Silva, Bide, Nilton Marçal, and Armando Marçal, and interpretations by vocalists like Mário Reis, Francisco Alves, and Carmen Miranda played an important role in solidifying samba as the national music of Brazil in the 1930s. This was also paralleled by a conscious effort by the highly controversial President Getúlio Dornelles Vargas to unify the nation and build a national culture through media, especially radio. Thus, the government, which had been stigmatized samba for its black roots, appropriated samba for its national identity.

As sambas gained popularity, various samba subgenres and styles emerged including samba-canção which emerged from more upscale neighborhoods in Rio and had a more melodic and harmonically advanced approach than typical sambas. Composers Noel Rosa, Braguinha, and Lamartine Babo, exemplify this style. Dorival Caymmi was the premier singer, songwriter, and musician to exemplify the style, as well as to master many other forms. His harmonic sensibility and advanced gutiar playing shaped the bossa nova that emerged in the mid-1950s. Samba-exaltaçãos, focused on the country’s beauty and richness, also emerged via composer Ary Barroso most famous for writing “Aquarela de Brasil” (“Brazil”). As sambas grew more popular, including being featured in films, and attracting new listeners and composers who blended it with other forms, purists began to rally around traditional samba. In the late 1950s, traditional samba thrived in the morros, the hills surrounding Rio, which also birthed the samba de morro style. Cartola, Clementina de Jesus, and Nelson Cavaquinho exemplified this approach.

Composer Ary Barroso wrote many of Brazil's most popular songs of the 1930s and 1940s in the samba-exaltaçãos style. His most notable song is "Aquarela Do Brasil" known to English speakers as "Brazil."

Actress and singer Carmen Miranda became the greatest popularizer of Brazilian crossover music via film and Broadway performances in the late 1930s-mid 1940s. She is pictured here circa the 1940s without her iconic costumes and jewelry.

Sambas transformed Carnaval, which in turn elevated the ongoing development of samba. The samba schools that began in the late 1920s became national institutions and sambas gradually displaced ranchos and marchas as the most Carnaval song forms. Samba de blocos, played by blocos de empolgacaos, typically close Carnaval parades.

The mid-1960s-early 1970s is the “modern” samba era where new generations continued to employ the form as a creative source. Singer/songwriters like Martinho da Vila wrote shorter and more colloquial sambas called samba-enredos. The 1970s also birthed the pagode movement. Pagodes were parties where people played samba, and within these parties musicians incorporated new instruments. Zeca Pagodinho and Jorge Aragão were key pagode voices. Dudu Nobre continued the style for new generations. Vocalists like Clara Nunes, Alcione, and Elza Soares, were also popular and respected singers who continued to maintain samba’s relevance. Other styles included samabandido (“bandit samba”) which depicted life in favelas and incorporated morro-based slang, and pop sambas which replaced the percussive style of pagode with funk rhythms, electronic instruments and more sentimental lyrics.

Singer-songwriter Martinho da Vila pioneered the samba-enredo form in the late 1960s, and is a popular musician known for exploring Brazil's musical richness, especially its African roots.

Elza Soares began recording in 1959 and remains an active singer and performer who continues to thrive singing samba based music.

Samba was integral to shaping future Brazilian genres including bossa nova, tropicália and música popular brasileira (MPB). A variety of social and political factors informed the birth of these genres. Next month I will continue to delve into these more contemporary Brazilian musical styles. Until then, please allow some of the samba recordings listed below to enter your ears and move your bodies, and check out some key educational resources.

Beth Carvalho was one of the pioneering voices in the pagode samba movement that emerged in the late 1970s.

Recommended Resources

Recordings (Formats vary; some are in CD form but many are available digitally and/or via streaming services):

Early samba

Pixiguinha

Raízes do Samba (2000, EMI)

Nelson Cavaquinho

Raízes do Samba (2000, EMI)

Samba-cançãos

Noel Rosa (composer and vocalist):

Noel Rosa: Versões Originais Vols: 1-5 (Featuring performances by Almirante, Francisco Alves, Carmen Miranda, João Petra de Barros, Mario Reis, and more, 2014)

Tributo a Noel Rosa Vol. 1 (Ivan Lins, 1997)

Tributo a Noel Rosa Vol. 2 (Ivan Lins, 1997)

Samba-exaltaçãos

Ary Barroso:

Ary Barroso em Aqueralas, Volume 1 (Various Artists)

Ary Barroso em Aqueralas, Volume 2 (Various Artists)

Carmen Miranda:

The Brazilian Bombshell: 25 Hits 1939-1947 (ASV/Living Era)

The Ultimate Collection (Prism Leisure, 2001)

Samba de morro

Composer Cartola was a composer and performer whose samba de morro songs are covered widely.

Cartola:

Raízes do Samba (2000, EMI)

Clementina de Jesus:

Euo sou o samba (EMI, 2005)

Samba-enredos

Martinho da Vila:

Focus: O Essencial De Martino da Vila (BMG, 1999)

Memorías de um Sargento de Milícias (BMG, 1971)

Lusofonia (Sony Music, 2000)

Modern Samba Queens

Clara Nunes:

Alvorecer (Odeon, 1974)

Clara Nunes 2 Em 1 [compiles 1974’w Alvorecer and 1981’s Clara] (EMI, 2005)

Alcione:

A Voz do Samba (Phillips, 1975)

Elza Soares:

Eusou O Samba (EMI, 2005)

Pagode

Beth Carvalho:

De Pé no Chão (RCA Victor, 1978)

No Pagode (RCA Victor, 1979)

Grupo Fundo de Quintal:

Samba e no Fundo de Quintal (RGE, 1980)

Zeca Pagodinho:

Zeca Pagodinho (RGE, 1986)

Millennium: Zeca Pagodinho (Polygram, 1999)

Jorge Aragão:

Verão (1983)

Jorge Aragão: Millennium - 20 Músicas Do Século XX (Polygram, 2000)

Dudu Nobre:

Dudu Nobre (BMG Brasil/RCA, 1999)

Neo-Pagode

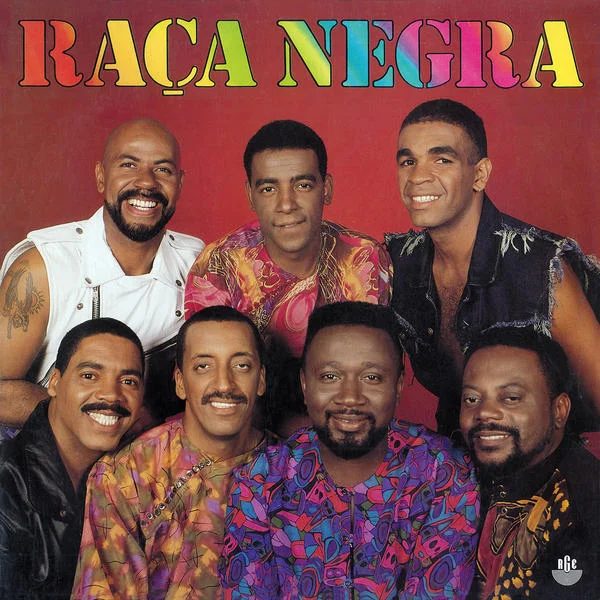

Raça Negra:

Banda Raça Negra (RGE, 1991)

The band Raça Negra is a neo-pagode band that added a modern sheen to the samba style in the 1990s.

Books:

The Brazilian Sound: Samba, Bossa Nova, and the Poplar Music of Brazil (Chris McGowan and Ricardo Pessanha, Revised and expanded edition, Temple University Press, 2009)

The Mystery of Samba: Popular Music and National Identity in Brazil (Hermano Vianna, University of North Carolina Press, 1999)

Making Samba: A New History of Race and Music in Brazil (MarcA. Hertzman, Duke University Press, 2013)

Creating Carmen Miranda: Race, Camp, and Transnational Stardom (Kathryn Bishop-Sanchez, Vanderbilt University Press, 2016)

Films:

Brasil! Brasil! Episode 1: From Samba To Bossa (BBC, 2007)

Link: http://www.musicismysanctuary.com/brasil-brasil-from-samba-to-bossa-bbc-documentary-part1

Carmen Miranda: Beneath the Tutti Frutti Hat (BBC, 2007):

Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MbTeIh1WGoQ

Mario Reis: The Mandarin (Director, Júlio Bressane, 1995)

Noel Rosa: Noel, o Poeta da Vila (Director, Ricardo van Steen, 2007)

COPYRIGHT © 2017 VINCENT L. STEPHENS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.