Learning to Listen Excerpt 15: k.d. lang: vocal sculptor

“You know there’s um, a lot of great entertainers and artists in the world. So many wonderful artists. Every once in a while there’s certain performers that come along. That they’re just blessed with a destiny. The three that come to mind are Billie Holiday, and Edith Piaf, Hank Williams. It goes beyond success. It becomes immortal. And I really believe the minute I heard this person sing that this is one of the artists that will go up on the shelf with them. Please welcome k.d. lang!”—Tony Bennett, from MTV Unplugged

The first time I saw k. d. lang (b. 1961) sing live was on a Comedy Central rebroadcast of a Saturday Night Live performance with her band The Reclines. lang, dressed in a purple pant suit with a mustard yellow blouse and ankle cut boots with her cropped haircut, sang the hell out of an archaically sexist song “Johnny Get Angry” with its chorus “Johnny get angry, Johnny get mad/Give me the biggest lesson I’ve ever had/I want a brave man/I want a cave man/Show me that you care that you care for me.” lang sang it in full-throated fashion hitting notes directly with a fervent almost operatic sweep; of course she sang the song with tongue firmly planted in cheek, at once screaming “Johnny!” and point flinging herself tothe ground. As she got up from her mock beat down she sang the song’s end in a faux operatic falsetto with her band chirping behind her “Go Johnny, Johnny!”

“Johnny” was originally sung by Joannie Sommers in 1962 with apparently less irony. Interestingly, though the song was a lang concert staple it was not featured on any of her albums so her performance seems more like a stunt and a statement than the usual promotional function of SNL performances. The stunning part of her performance is the tension between the robust quality of her voice—hearty, full-throated, controlled—and her cheekiness. Because she plays its straight she is able to sustain the “joke” and actually earns the histrionic coda. She knows that we as her audience are in on the joke. This allows her to underplay the song’s sexist abusive sentiments just enough that we can distance ourselves from the song, and mock it, while also confronting how sadly “ordinary” its misogynist premise was in the ‘60s—and perhaps in 1990 too.

Vocalist, writer, and interpreter extraordinaire k.d. lang.

Like many country and pop divas of the time lang was a potent vocalist. But she was also a dynamic performer, a kind of character unafraid to harness her voice to her worldview, rather than merely use it in service of the traditional romantic sentiments of diva pop. There’s a conceptual energy and political undercurrent to her “Johnny Get Angry” missing from much of the country milieu she was initially identified with at the time. During the 1980s she and Lyle Lovett injected country with some much needed irony, humor, and self-awareness that ultimately modernized it. Dwight Yoakam, K.T. Oslin (see chapter), Rosanne Cash, and Mary Chapin-Carpenter also modernized country. Among these artists lang is the one who has most successfully transcended genre and era.

Though lang’s androgynous appearance and gender neutral pronoun-laced love songs should have made it obvious that she was not a traditional country vixen, her Ingénue-era coming out as a lesbian freed her sexually and musically. In her earliest work she sounds like a gifted vocalist with more voice and concept than she can fully sort out; she initially presented herself as the reincarnation of Patsy Cline (hence her band’s name The Reclines) and sang more as a character than a singer. This was not a problem when lang was a cowpunk and neo honky-tonker, particularly in her interpretations which were often covers of light hearted, sentimental ballads and waltzes with a florid romanticism and precious imagery. But as a composer a natural sense of romantic melancholy, social empathy, and emotional unrest emerged in her writing that was too strong to be compartmentalized.

Her first mature recording Shadowland is a lusciously textured mix of torch songs and corny, old-fashioned country tunes she manages to make palatable. It is an accomplished and often affecting album with singing, arrangements, and vocal quality easily placing it in the upper echelon of pop and country albums of 1988. At times, however, it feels more like a stunt or an experiment in its vacillations from serious ballads to novelty songs and lang’s elusive persona. She sings like a pro but almost never surrenders to her material maintaining a distance even in her most emotional and convincing performances. The one exception is the final song a “Honky Tonk Angels Medley” sung with country pioneers Brenda Lee, Loretta Lynn, and Kitty Wells where she plays more of a supporting role and sounds genuinely in the moment reveling in the impressive company. Here she is just one of the girls, but elsewhere she sounds suspended between giving the songs the technical acumen they require, including tonality, but I sometimes sense that she is more entranced by the style of emoting the songs represent than feeling deeply connected to them.

Her performances of “Shadowland,” “I Wish I Didn’t Love You So,” “Busy Being Blue,” and especially “Black Coffee,” are masterful ballad performances sung with an ache approaching her role model Cline, as well as torch bearers like Holiday and Sinatra. In these performances she masters the countrypolitan elements—lush strings, cooing choirs—producer/arranger Owen Bradley frames her with, but despite the seemingly old-fashioned settings she never sounds imitative. She actually finds her own sound within the generic style. She also manages to sing cornball songs like “(Waltz Me) Once Again Around the Dance Floor” and “Don’t Let the Stars Get in Your Eyes” affectionately rather than mocking them; yet there is a clear sense of distance between her and them. lang sounds more intrigued and bemused by the innocence they possess than challenged or invigorated by the songs themselves.

Ultimately Shadowland is a successful recording in execution, but is limited by design. lang proves she has the voice and technique to capture the countrypolitan aesthetic—a juxtaposition of raw emotion with lush landscapes that cushion singer and listener, lest things get too raw. But it is precisely this boundary that she wants to break from. What’s missing from the album is any real sense of adult sexuality. lang sings with a sensuous throb, and devours melancholic lyrics but there is a sexlessness to the album that does not seem sustainable. The expert pastiche she and Bradley achieve is impressive not expressive in a personal sense; lang could have easily could duplicated this approach and become a lounge act or a postmodern country act in the way that neo-“swing” bands did in the late 1990s. Fortunately she began to break free from the amusing, but disconnected asexual character her recordings presented and moved closer to capturing the bold, sassy persona of “Johnny.”

Of the 12 songs on 1989’s Absolute Torch and Twang nine were originals, with eight co-written by lang and her collaborator Ben Mink, and one written by lang exclusively. Having mastered countrypolitan she returned to the cowpunk attitude of her earliest albums, A Truly Western Experience and Angel with a Lariat. The resulting album sounds like an extension of who she is rather than a representation of what she can do, and the results are liberating.

On the Bo Diddley-esque “Luck in My Eyes” she sounds emotionally and sexually invigorated; there’s steadiness to its backbeat, optimism in its harmonies and intrigue in her voice that feels completely unguarded. Her version of Willie Nelson’s “Three Days” swings and extends “Luck”’s optimistic theme in its propulsive rhythm and her involved vocal. Elsewhere she conveys a stinging gutsiness of persona in “Didn’t I” and the anthemic “Pullin’ Back the Reins.” It is usually a folly to interpret lyrics too deeply as pure autobiography, but there is a thematic consistency here that evokes the bold personae country predecessors like Kitty Wells, Loretta Lynn, Tammy Wynette, Wanda Jackson, Dolly Parton and Rosanne Cash previously authored in their lyrics. These songs quickly dispel any notion of lang as a closed book; she remained an impressive technician and a versatile stylist, but she was branching into a distinctive sound. Elsewhere she paints an affectionate portrait of an outsider who finds acceptance on “Big Boned Gal” appropriating the elements of country corn for more incisive purposes than sexual innocence or pastiche.

In addition to authoring her versions of torch balladry (“Trail of Broken Hearts,” “Wallflower Waltz”) lie two songs poignantly relevant to her eventual notoriety for gender ambiguity including her plaintive take on the illusion of star personae “It’s Me,” and a searing view of child abuse (aka “discipline”) on “Nowhere to Stand.” On “It’s Me” she sings plainly “I am givin’ what I can” and “Might not be all you want/But it’s all you get it’s me,” in a sense indicating the sense that she will neither define herself in other’s terms nor apologize for the ambiguity she presents. This could be heard as a proto-coming out anthem, but its scope seems broader, a simple anthem exposing the tolls of public/private tensions and the resignation it can inspire. “Nowhere” unmasks the dark, buried elements of “small town” lore particularly questioning the common sense attitude toward “order”: “A family tradition/The strength of this land/Where what’s right and wrong/Is the back of a hand/Turns girls into women/a boy to a man.” By ending the set with this sobering look at a complacent mentality regarding man-made morality and the questionable social elements its props up, she manages to work within country music’s tradition of plaintiveness and to question the “values” it represents. Just as Shadowland demonstrated her finesse with countrypolitan and tacitly earned her the endorsement of established country figures, Absolute Torch and Twang allowed her to synthesize her mastery of various forms of country tradition and test her ability to contribute to it personally.

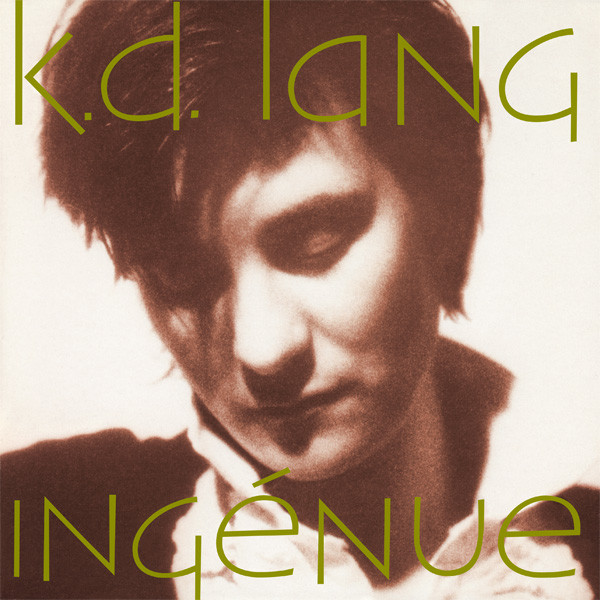

After years of postmodern cowpunk and country lang had a pop breakthrough with 1992's sumptuous suite of longing Ingenue.

Her move toward pop music on 1992’s Ingénue and 1995’sAll You Can Eat allowed her to expand on her growing confessional persona in different and possibly less constraining musical settings. Though country music is rife with subgenres (honky tonk, The Bakersfield Sound, countrypolitan, western swing, etc.) commercial momentum in the genre is increasingly dependent on artists’ ability to adapt to radio trends that homogenize their sound, but keeps them sounding “current.” Country lyrics and rhetoric may be big on tradition, but at any given moment the genre is rife with veteran artists who have resigned themselves to commercial obscurity. This became profoundly true in the early 1990s when Sound Scan digital retail technology revealed the wide commercial market for country, exemplified by Garth Brooks, and later solidified by Shania Twain, Faith Hill, Tim McGraw and other contemporary country acts. With rare exceptions iconoclastic country acts mostly turned to the folk and “roots music” circuits (see Chapin-Carpenter, Rosanne Cash, Emmylou Harris, Lucinda Williams, and Dolly Parton) or have been fortunate to have admirers in the rock world to boost their careers (i.e. Loretta Lynn’s 2004 comeback Van Lear Rose produced by the White Stripes’s Jack White).

lang avoided this by moving toward what could loosely be called the “adult contemporary” market—shorthand for well-heeled middle aged listeners who listen to the radio at home, or on their daily commutes, and are prone to buying albums. Though pop music and offshoots like “soft rock” and “adult contemporary” are usually derided pop’s elasticity allows it to be constantly redefined and reconfigured, making lang’s transition sensible. If she continued moving in the compositional direction reviewed on Absolute she would have eventually been steered toward the folk/roots music circuit so it’s fortunate that she chose to expand her sound, flying free of country genre conventions.

lang has redefined herself with each album. Her initial albums A Truly Western Experience, Angel with a Lariat and Shadowland were experiments that showcased lang in an array of country guises. Though each is enjoyable in its own way and more listenable than its predecessor, Absolute Torch and Twang was the fullest reach into her potential as a significant writer and personality in country. But her decision to disassociate from country almost seems inevitable; country is so steeped in tradition that even those most capable of pushing it forward may feel intimidated by their own potential. Additionally, the androgynous, unapologetically singular, avowedly unique lang has expressed a sense of rejection from industry figures in the genre in interviews which made her transition to adult pop music a charmed one. Since ending her country phase lang’s sound can be understood as emerging from a constant series of gradual shape shifting and resculpting, fostered by her chosen themes and arrangements.

The Great Melding: The Many Voices of k.d. lang

Ingénue: The Yearner

On Ingénue lang gets naked—exposing all of her desires, anxieties and insecurities in a seamless melding of styles that flow throughout her musical soul. Her singing is intimate and open hearted, and her songs allow her to wield her formidable voice in settings both flattering to her voice and revealing of the vulnerable soul within her. Though nominally viewed as a “pop” album it’s actually a “soul” album in the traditional sense of revelation.

In another vein, though, it could be viewed as a move toward “pop,” but not in the modern sense of disposable, trendy music manufactured for radio. Having spent her career dashing between country-flavored novelties and torch ballads, lang assimilated these conventions into a singular style. Ingénue sublimely fuses lang’s eclectic musical passions into a dense meditation on unrequited love. There are traces of country, cabaret, folk, jazz, and pre-rock pop but it never feels calculated or patchy. By allowing elements of these genres to color her writing and arranging process there is a mosaic-like quality that give it an unusual integrity; it’s like block of melancholia rendered in the most sensuous of shades.

She humorously questions her sanity (“Talking to myself dear/Is causing great concern for my health”). Yearns to be freed from the burden of desire (“Save Me”)…captures the giddy lift of love (“I can’t explain/ Why I become Miss Chatelaine”)…on “Constant Craving,” her biggest pop hit, she expresses a universal emotion with a sweep too impassioned and personal to feel ironic and too potent to lapse into sentimentality. Once she has finished singing and you have finished listening there is no turning back. Something has been opened and her progression feels inevitable.

The open-throated “Constant Craving” is a fitting end for an album of such deep yearning. The song unleashes a virtual decade of bottled up emotions. It depicts a quintessential expression of her journey toward voicing her own truth. The album’s aesthetic achievement set the pace for her subsequent albums in terms of the diversity of styles and textures, the potency of her singing, and the soul revealed in her lyrics.

All You Can Eat: The Lover

If lang’s earliest country albums skirted desire by burying her emotions in skillful pastiche, and Ingénue articulated her profound hunger to be loved, she transitioned from yearner to lover on the tongue-in-cheek All You Can Eat. It is an emotional feast centered on embracing love and sex wholeheartedly. Favoring a sleeker, more modernized approach to arranging and production—drum loops, keyboards, and programmed funk grooves are quite prominent—she also streamlines her singing just enough to convey a cool remove, but potent enough to hint at a latent, simmering sensuality. Songs like “Sexuality” (“Release your sexuality/On meeeee”), and “Get Some” (“Go on/Get some/Take all that you’re given/Just go on/Get some/Get some of the love you’re giving someone”) have a casual erotic edge to them that fully ripens on the final track “I Want it All.” Whereas “Constant Craving” mapped the heartbeat of aspiration “All” is a throbbing, lustful statement that earns its climactic finish (“I want/I want/I-I-I-I want it allllll”).

In between Ingenue’s much heralded success and All You Can Eat lang recorded two duets with Tony Bennett on his MTV Unplugged TV episode and album. lang had some experience collaborating in a country vein including her dynamic duet on Roy Orbison’s “Crying” with Orbison himself and a sassy cover of Gram Parson’s “Sin City” with Dwight Yoakam. But MTV Unplugged was the first indication of her promise as an interpreter of American Songbook material.

lang delved more deeply into the joys of sensuality on 1995's All You Can Eat.

Drag: The Torch Singer

Whereas other popular singers like Carly Simon, Linda Ronstadt, and Natalie Cole previously recorded “Songbook” style albums earnestly lang approached this collection of songs conceptually as a suite of “smoke” themed songs—love as a kind of unhealthy addiction. Hence she included established standards like “Don’t Smoke in Bed” and “Smoke Dreams,” as well as more modern fare like Jane Siberry’s “Hain’t It Funny” and her gender inverted version of Steve Miller’s “The Joker.” One of lang’s gifts as an interpreter is her manipulation of tone; she can sing in a straight, sincere manner and with a winking sense of irony in the same song, but never condescends to her material or her audience. The notion of love as a kind of trap we fall into and constantly climb out of only to return has an inherent absurdity and truth her performances uncover. By eschewing obvious torch material, sparsely employing strings —thanks to Craig Street known for his ascetic productions for Cassandra Wilson—and focusing on a penetrating ballad style she steers clear of rock torch clichés (i.e. bland mood albums, wan jazz pretenses) and creates something distinctly modern: a singer who has an acute sense of humor about love’s absurdities and a genuine sense of ache that never cancel each other out.

Invincible Summer: The Companion

In the midst of her burgeoning recording career lang cultivated a romantic relationship and took a break from recording. The emotional transformation experienced through companionship and domesticity permeates the blissed out vibe of Invincible Summer. Here lang salutes ‘60s surf music and light pop, with its focus is on buoyant, energetic songs and lushly harmonized balladry. Summer is among her more commercially obscure and least heralded albums; perhaps because it’s so casual and laidback its mellowness belies the intense emotionalism and torchy style that her listeners of have become accustomed to hearing. It is less compelling than her previous work, but still quite endearing as a listen particularly the cacophonous lead single “Summerfling” and the deliciously woozy “Consequences of Falling.” The album’s most enduring composition is “Simple” co-written with bassist David Piltch. Here the album’s core theme and lang’s discernible sense of contentment is at its most lucid. If anything this set reiterates the reach of her songwriting abilities as well as the immense flexibility of her voice. Further despite the lighter tone of the set it represents a shift in lang’s musical personae as it marked the last album of compositions for eight years, as she turned more fully toward interpretive singing.

Live By Request: The Stylist

By 2001 lang had attained enough of an audience, as well as sizable industry respect that A&E showcased her on its Live By Request series in which singers sing material from a list of rehearsed songs chosen by viewers. One does not need to be intrigued by the gimmick to appreciate the raw display of vocal refinement and personality exhibited on the album version. Having recorded country, pop, and rock standards, and written original pop and country flavored material lang had a sizable repertoire to choose from and this resonated with her fans. Nominally a de facto compilation it is highlighted by lang’s robust performances including her explosive solo version of “Crying,” and her wrenching interpretation of “Black Coffee.” On stage before her audience she duplicates the precision of her recordings, but infuses it with an effervescent presence—a sense of dynamics that makes each performance individually exciting and that presents her as one of modern pop’s most versatile stylists.

Though the term “stylist” sometimes refers to eclectic singers too lazy to delve deep into different genres beyond their surface, lang is a deeply musical, genuinely eclectic musician with a remarkable sense of flexibility. In addition to this lang projects a maturity that signals a new phase in her career as an adult entertainer. At worst the “adult” music label usually refers to gaudy, aging lounge lizards, but in this context lang wows you listener with her technical precision and emotional resonance, and her sense of space. For example on the TV special she dons a dress and wig and serenades the audience with a perfectly over-the-top version of “Macarthur Park” that goes just far enough to remind her audiences of her cheeky performance artist past before singing the next song. There is a sense of balance, diversity, and pacing to the overall performance that makes her shift toward interpretive singing logical; in many ways she sounds like one of the few singers of her generation who could genuinely succeed the balladeers and torch singers of the pre-rock era—in terms of talent and refinement—but in a manner transcending nostalgia. Though swing is a minimal influence in lang’s recordings she sings with such poise and power she would not be out of place in such a setting.

A Wonderful World: The (Solo) Interpreter and Collaborator

Crooner and swinger Tony Bennett has been enjoying a much deserved commercial and artistic rebirth since 1992 and he has consciously shared his fortune with other vocalists, especially lang his most frequent duet partner. After duetting with her in 1994 and on his 2001 blues themed album Playin’ with my Friends (where lang demonstrated only a mild talent for the blues on their version of “Keep the Faith Baby”) they collaborated on A Wonderful World a tribute to Louis Armstrong featuring lang and Bennett’s renditions of signatures like “What a Wonderful World” and “A Kiss to Build a Dream On.” Because Bennett has always been more of a singer influenced by swing than an improvising jazz singer he is most appealing when he works with jazz-oriented vocalists and/or arrangers who push him to take more risks. Because lang is primarily a balladeer they complement rather than challenge each other on this largely orchestral, slowly paced set which makes for a listen more enjoyable than emotionally penetrating. They have playful chemistry on the lightly swinging opener “Exactly Like You” and lang has some particularly radiant, playfully ethereal vocal moments on “Dream a Little Dream of Me.” Both performances indicate that she could easily make a full-time career as an interpreter of “American Songbook” material if she chose.

Functionally lang—who performed a stirring “Skylark” on the Johnny Mercer-themed Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil soundtrack—“proves” that she can sing romantic material in a straightforward and appealing manner over the course of an album. And that she can confidently and comfortably sing alongside an iconic voice like Bennett’s without embarrassment. This set was critically well-received and commercially successful—particularly for a “vocal pop” album. It also imbued her with credibility as an interpreter with a seemingly boundless musical scope and a sense of talent and taste that had attracted some of the industry’s most respected figures. Few popular singers in recent memory have blazed such a path from country to pop to traditional pop interpretation so seamlessly. By 2003 lang had earned Country Grammies for a duet with Roy Orbison (“Crying”) and Absolute Torch and Twang, a Pop Vocal Grammy for “Constant Craving” and a Traditional Pop Grammy with Bennett for A Wonderful World. In a 15 year period she was one of the few singers of her generation who was widely respected for her ability to sing in almost any type of song successfully whether it was country, rock, or a pop standard.

Hymns of the 49th Parallel: The Progressive Interpreter

lang oriented her promise as an interpreter of American songcraft toward the art songs of her native Canada on Hymns tackling pantheonic songwriters like Joni Mitchell, Neil Young and Leonard Cohen, alongside more recent writers like Jane Siberry and Ron Sexsmith among others. The result is an original collection of material indicating a progressive sense of interpretive repertoire in a vein parallel to recent developments among jazz singers looking toward rock era pop for suitable vehicles for interpretation. The set is ballad heavy and the orchestral settings are lethargic compared to Drag, but lang manages to find new life in some of pop’s most well-worn songs. Notably, she sings Cohen’s “Hallelujah” with stunning pacing building to an epic, but well-earned climax that completely uplifts the song. It has subsequently—and rightfully—become an anthem for lang who mesmerized audiences at the 2010 Winter Olympics with a dynamic full-throated live version. Comparatively she massages “A Case of You” with the intimacy of two lovers conversing, and reinterprets her original song “Simple” (originally recorded for Invincible Summer) placing it in a context that makes it sound more timeless than its 2000 vintage would suggest. She performs similar interpretive feats on her rendition of Young’s oft-covered “After the Gold Rush” which is performed with a clear eyed sense of wonder and bewilderment, laced more with shock and discovery than naïveté.….

lang exhibited strong rock roots on 2011's Sing it Loud.

Future

lang’s frequent stylistic shifts make her a delightfully unpredictable talent. In 2010 two collections, Reintarnation (country themed) and Recollection (more comprehensive), summarized the major highlights of her career, including special material recorded for soundtracks like the majestic “Calling All Angels” (from Until the End of the World soundtrack) harmonized with Jane Siberry and her smoldering version of Cole Porter’s “So In Love” (recorded for Red Hot + Blue). The total sum of these presents such a wide array of colors that her career could shift in any direction.

After about a decade of flirting with traditional pop and returning to songwriting on the subdued Watershed, lang is energized on 2011’s Sing It Loud whose rock-ish edge evokes her cowpunk roots. Thanks to her new band Siss Boom Bang she has regained her voice. Sing features a beefier sound with revving guitars, thumping drum beats, big crescendos, and hearty crooning belting that balance pop and rock instincts astutely, with traces of country and even R&B. lang croons in a sensual, almost boozy manner. Her melodies are bolder and her lyrics are more visceral than they have been since 1995’s All You Can Eat. Highlights include the anthemic title track, the sensuous opener “I Confess,” and the closing shuffle, “Sorrow Nevermore” a memorable self-affirmation….

In between 2004’s Hymns lang released Watershed (Nonesuch Records, 2008), comprised of original highly reflective compositions in laidback acoustic settings. Her most recent album is 2016’s case/lang/veirs (Anti/Epitaph) a folk-rock set recorded with Neko Case and Laura Veirs.

COPYRIGHT © 2016 VINCENT L. STEPHENS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.