Pop singer deaths—you’re killing me: On the deaths of pop musicians and our fragile personal canons

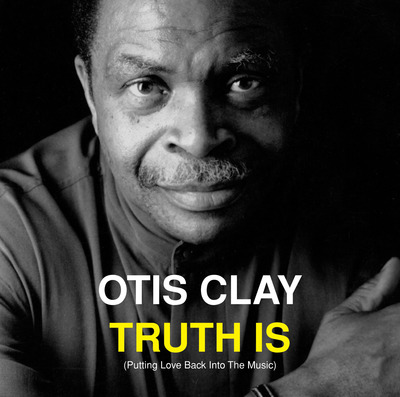

In my inaugural Riffs, Beats, & Codas blog post (in February 2015) I addressed the deaths of Whitney Houston and Michael Jackson emphasizing how longstanding aspiration for black singers to “crossover” diminishes their sense of reality and health. I revisit death this month because since the beginning of 2016 David Bowie, Otis Clay, Natalie Cole, and Glenn Frey are among the popular singers who have died. By almost any quantitative metric their deaths have inspired established old fans, and attracted new fans, to purchase their recordings (Bowie’s release Blackstar debuted at #1 on the Billboard 200—his first), watch videos on YouTube (my favorite is a gospel charged duet between Houston and Cole on “Bridge Over Troubled Water”), and craft multimedia tributes to their artistry. While I won’t do that here (I posted an essay on Cole from Learning to Listen in January), this strange onslaught of deaths reminded me of an episode from a few years ago.

Image source: www.davidbowie.com.

In 2010 I was attempting to draft an essay on one of my favorite musicians of all time, Phoebe Snow, whose “Poetry Man” grabbed my ear as a child, and whose fluid phrasing has forever held me under her spell. I couldn’t remember a detail and did a Google search only to discover that she was hospitalized for a stroke. She died shortly after my search and I was stunned. How did I not know that she was sick? I had recently purchased a stellar 2008 live album (Phoebe Snow Live, Verve Records) and remained in awe of her range, versatility, and soul. How could her voice be muted?

Image source: otisclaystorenvy.net.

Part of my sadness was the loss of a great singer, as well an abrupt reminder that I was aging as. This sounds obvious, but singers are a gauge for mortality because they are touchstones of our existence. We grow up with them and age as they age. We live through their promising debut albums, their navigations of trends, their fashion mistakes, their childish feuds with other singers, and their ill-considered musical experiments because we love their music and what they represent to us.

Image source: glennfreyafterhours.com.

When I revisited Bonnie Raitt singing, “I see my folks they’re getting old/I watch their bodies change/I know they see the same in me/And it makes us both feel strange” (in 1989’s “Nick of Time”) at some point in my 20s I lost my innocence about aging, and death. Which is to say the big gap I imagined between my parents and myself shrank suddenly. I was no longer the “kid” far removed from the inevitable, but part of the adult world comprised of people hoping to survive. Since I use my parents’ ages as another gauge of “old” and “young,” like a mental security blanket, seeing people younger than my parents die, especially pop singers, who always seem immortal and inevitable to the young, was stunning. If “star x” dies other treasured musical/cultural touchstones could pass as well. Musicians’ deaths, as well as those of other artists, reveal the fragility of our personal cultural universe. When our heroes and benchmarks and inspirations pass away our part of our world diminishes. And who will replace them? Can they be replaced?

Pop music listeners tend to experience a growing gap between the music we discovered, mastered, and grew up with, (“our music”) and what’s popular in the mainstream. As I wrote in my October column (“‘My’ music and theirs”) it’s hard to keep up with the mainstream sometimes and we get easily set in our ways. We can admire some new music but it fights to secure a place in our personal canon. Or, we are willing to integrate the new as long as it is somewhat recognizable and fits within what we value formally. For example, rock critics warmed up to U2 in the 1980s and Coldplay in the 2000s because their music and politics reminded them of “classic” rock groups so they’re easier to embrace than more radical bands outside of rock.

This concern about canons is more of a middle aged-and-beyond issue, but it will reach the “young” soon enough. For someone like myself, who was born in the mid-1970s and came of age in the 1980s and early 1990s, a lot of the music popular during my youth was made by singers born in the 1940s and 1950s. As we approach 2020 many of these singers are aging gracefully and still thriving artistically (i.e. Patti LaBelle, Maria Muldaur, Aaron Neville, Barbra Streisand), even if they are understood as “heritage” artists. Others, like Linda Ronstadt, have been silenced by disease, or have declining vocal resources, but the blow is softened by the volume of great music they have recorded. Singers born in the 1960s and 1970s (i.e. Mary J. Blige, Boyz II Men, Mariah Carey) have only reached middle age, and yet they struggle continually to balance their natural talents and styles with the pop imperative to remain current.

Image source: www.billboard.com. Photo by Bobby Bank/Wireimage.

The death of a musician, or actor, or dancer we admire, but never knew, operates differently than the deaths of partners, relatives or friends. But where those are usually mourned very publicly and ritualistically within communities, the death of an artist is mourned differently to a person. While there are many ways to pay tribute to artists through the written word and visual homages, there’s also an internal disruption of order, like displaced chess pieces. Thinking about the deaths of Jackson, Houston, or more recently blues icon B.B. King, I’m reminded of those moments when I hear a song by them and I’m startled into remembering they’re no longer here. I can relish their memory in my head but I have to move on with my ears.

COPYRIGHT © 2016 VINCENT L. STEPHENS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.