Ear adjustment: Exploring the untold history of Black Music

In 1979, President Jimmy Carter inaugurated June as Black Music History Month, which President Barack Obama renamed African-American Music Appreciation Month in 2009. Though the concept of “black” music could apply to any kind of music performed by black people technically, we usually tend to understand it in terms of genre. Artists associated with hip-hop, R&B, reggae, blues, jazz and gospel are usually the starting point for conversations about intersections of blackness and musicianship. The historical emergence of these genres from black subcultures, ranging from the derivation of gospel from the West African “ring shout” to the post-industrial urban context that wrought hip-hop, defines this iconic association.

Yet, just as blackness as an identity, culture and realm of experience, must be understood beyond conventional wisdom, the music created by black musicians must be understood complexly. Music is a compelling space for uncovering obscure, or forgotten, artists whose stories tell a fuller richer story of blackness than usual.

Harmonica player Deford Bailey (1899-1982) was the first black superstar in country music.

For example, most listeners primarily associate country music with Southern white musicians and audiences. Though many people are aware that artists like Ray Charles and Charley Pride broke color barriers in country music, and Hootie & the Blowfish frontman Darius Rucker has become a solo country star, there’s more to the story. The 1998 three-disc set From Where I Stand: The Black Experience in Country Music introduced me to important figures rarely discussed in mainstream black music conversations. For many years, I thought jazz musicians were at the forefront of musical integration in the recording industry. In fact, Taylor’s Kentucky Boys, an integrated string band comprised of black fiddler Jim Booker, guitarist John Booker, banjo player Marion Underwood, guitarist Willie Young, and occasional vocalists, did the first racially integrated recording sessions in a studio in 1927.

The geographic and cultural proximity of black, white and Native American musicians living in the South birthed a more diverse brand of Southern music than most people realize. There was a proliferation of string bands, like the Georgia Yellow Hammers, the Dallas String Band, James Cole String Band, and others, as well as solo performers.

The Carolina Chocolate Drops are a contemporary band keeping the string band tradition alive through playing classic and contemproary songs.

Harmonica player Deford Bailey (1899-1982) was the first African-American musician associated with the Grand Ole Opry’s radio program, from 1926-41. He also appeared on the Opry’s 1939 television debut on NBC’s Prince Albert Show. Despite these monuments he was not accepted fully, and experienced being referred to as the Opry’s “mascot” as well as the denial of service at restaurants and hotels when her toured small towns. While racism is a familiar trope in discussions of black musicians of his generation, less familiar is the way blacks who grew up in the Southern U.S. listened to country music and often emulated radio artists. Bailey’s grandfather was a fiddler, and Bailey got his big break after white string band leader Dr. Humphrey Bates recommended him to the producer of the WSM “Barn Dance” radio show, which became the Opry. Though these cross-cultural alliances were not necessarily typical of the industry a gradual cross-pollination took shape especially in the post-WWII era. Many of the musicians included on the set discuss their appreciation for the music and lyrics of country music, viewing it as a parallel to the blues. There are also important voices represented on the set, like Dobie Gray (1940-2011; famous for 1973’s “Drift Away”) and Bobby Hebb (1938-2010; who wrote the 1966 hit “Sunny”), who have defied genre rules throughout their careers and challenged conventional wisdom about the sound of black music.

Odetta (1930-2008) was the arguably the most influential folk musician of her generation.

Folk music is another genre with a strong black presence. The more recent success of Rhiannon Giddens and her band the Carolina Chocolate Drops is a great link to the past. Before performers like Giddens, and Tracy Chapman, whose 1988 debut was an unexpected pop hit, there was the legendary Odetta (1930-2008). Classically trained as teenager Odetta performed in musical theater as a young adult before turning to folk music in the 1950s. After establishing herself on the nightclub circuit she became a prolific recording artist recording for the Tradition, Vanguard, Riverside and RCA Victor labels. Her recordings and performances, were complemented by her vigorous civil rights activism. Odetta was considered the premier folk singer of her generation and influenced performers like Joan Baez, Harry Belafonte, Bob Dylan, and Carly Simon.

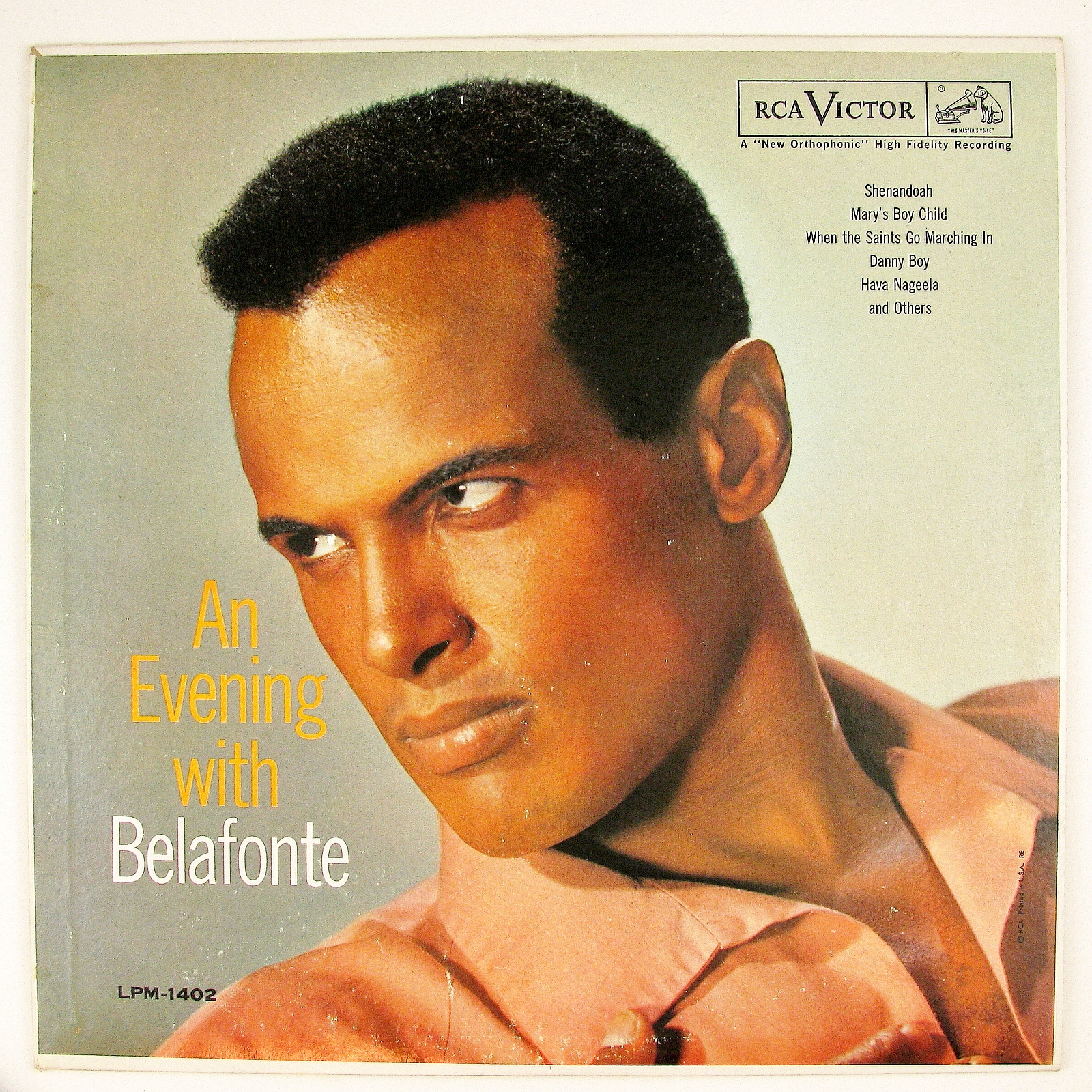

Harry Belafonte's (1927-present) dynamic concert performances and popular albums mainstreamed folk music from multiple countries including Trinidad, Israel and Peru. He was also a successful stage, film and TV actor, and producer.

Other black superstars of the 1950s who influenced folk performers include Harry Belafonte (1927-present) whose dynamic performances and popular recordings of folk music from Jamaica, Trinidad, Peru, Israel and other countries made him the first world music superstar. He was also integral to introducing U.S. audiences to the South African singer and activist, Miriam Makeba (1932-2008), known as “Mama Africa”. A gifted singer, composer, and actress, and a fierce anti-apartheid activist, Makeba began performing in the U.S. in 1959 and began a successful recording career on RCA in 1960. She committed her life to her music and her activism and performed until the very end of her life.

Just as the southern rural black experience is rarely discussed, beyond country blues and delta blues musicians, the presence of blacks in the chic, sophisticated world of New York cabarets, a thriving cultural space form the 1930s-1960s is also elided. Cabaret singing is an intimate style of singing performed by stately but highly distinctive, often idiosyncratic singers who frequently focus on the Great American Songbook and obscurities. Well-known black singers like Pearl Bailey, Sammy Davis Jr., and Eartha Kitt have roots in cabaret. There are, however, are many others who never crossed over to mass audiences through TV or film.

Mae Barnes (1907-96) was one of the most well regarded performers in the New York cabaret world.

One of cabaret’s most successful performers, Barbra Streisand began her career performing at the Bon Soir in Greenwich Village. But long before her there was Mae Barnes (1907-96) an African-American singer and dancer who was so popular the club was referred to as the Barnes Soir. Combining elements of Broadway, Vaudeville, and jazz in her live performances, and famous for her wit she was highly revered and rarely recorded.

Mabel Mercer (1900-1984), born to an African-American father and English mother, grew up in Europe before immigrating to the United States in the 1940s. Famous for her perfect diction, rolled “R”s, and incomparable readings of lyrical nuances she was adored by composers like Bart Howard (“Fly me to the Moon”) and Cole Porter. Mercer was the queen of cabaret who influenced singers like Frank Sinatra and Tony Bennett, and held court at legendary clubs like Tony’s, Ruban Bleu, the Byline Room, and others. The St. Regis Hotel named a room after her in 1975; ion 1984 Stereo Review magazine established the Mabel Mercer Award to honor outstanding musicians, and in 1985 the Mabel Mercer Award Foundation was established.

If Mercer was the Queen of cabaret Bobby Short (1926-2005) was the undisputed King. Born in Danville, Illinois he was a gifted pianist and distinctive vocalist who became a successful child performer in Chicago and then began performing throughout the U.S. and Europe. Known for his throaty voice, vast repertoire, and rapier wit he became a mainstay at the Café Carlyle from 1968-2004, and enjoyed a long recording career at Atlantic Records. He also recorded five albums for Telarc Records from the 1990s-2000s. Other notable black cabaret figures include Josephine Baker, Thelma Carpenter, Jimmie Daniels, and Leslie Uggams.

Contemporary black performers with a background in cabaret include actor-singer Darius de Haas, Broadway actor Norm Lewis, Tony Award-winning actress Audra McDonald, and vocalist Paula West. Since cabaret is more of a performing genre than a recording field many cabaret-oriented singers are also actors. Related to cabaret then, is the history of black performers who have excelled in musical theatre on Broadway. This distinguished roster includes Belafonte, who won a 1954 Tony for his performance in John Murray Anderson’s Almanac, Sammy Davis Jr. who was acclaimed in 1964’s The Golden Boy, Eartha Kitt, nominated for Tonys for her performances in 1978’s Timbuktu! and 2000’s The Wild Party, Billy Porter’s role in 2013’s Kinky Boots, Lewis and McDonald, who performed together as leads in 2014’s The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess, and the more recent triumph of actor-singer Leslie Odom Jr. in his Tony winning role in Hamilton.

Jubilant Sykes is one of America's msot talented and acclaimed baritones.

Classical music is another arena where the contributions of black musicians are often overlooked. In the vocal field female singers Marian Anderson (1897-1993), Leontyne Price (1927-present), Jessye Norman (1945-present), and Kathleen Battle (1948-present) are important figures with popular notoriety. Notable male voices include legendary actor, singer and activist Paul Robeson (1898-1976) and baritone Robert Todd Duncan (1903-98) who originated the role of Porgy in Porgy & Bess in 1935 as well as the role of Stephen Kumalo in Kurt Weill’s 1949 production Lost in the Stars. Some more contemporary figures include baritone Jubilant Sykes, and more emergent male vocalists including Jamaican born baritone Rory Frankson, lyric tenor Lawrence Brownless, and tenor Issacach Savage.

Baritone Robert Todd Duncan (1908-98), pictured here with actress Anne Brown, originated the role of Porgy in Porgy & Bess.

In the classical instrumental field there are many black musicians worth discovering such as Anthony McGill, principal clarinetist of the New York Philharmonic, as well as notable organizations dedicated to diversifying the field. For example, the Sphinx Organization’s focus on training and developing underrepresented young musicians has culminated in the renowned Sphinx Virtuosi comprised of Black and Latino musicians. The website AfriClassical was also begun in 2000 to chronicle the history of people of African descent in classical music.

Sphinx Virtuosi (Photo by Kevin Kennedy) has changed the face of contemporary classical music.

Anthony McGill is the Principal Clarinetist for the New York Philharmonic.

Any legitimate effort to explore black history comprehensively requires exploring unheard and overlooked figures. The relevance of Black History Month lies in the ongoing opportunity to expand our understanding of the stories, experiences and achievements of blacks in America. Music is an important dimension for the music itself, and the histories that inform its creation and reception. It is no coincidence that many of the musicians listed above, like Marian Anderson, Paul Robeson, Belafonte, Odetta and Makeba are as well known for their activism as their music. Theirs is a story worth exploring for the way it speaks to a larger richer story of the historical contours of blackness in America.

Additional resources:

AfriClassical website: http://chevalierdesaintgeorges.homestead.com/

"Black Men Storm the Gates of Classical Opera": http://www.ebony.com/entertainment-culture/black-men-storm-the-gates-of-classical-opera-323#axzz4XpI5EogN

Mabel Mercer Foundation: http://www.mabelmercer.org/

"Six African American Country Singers Who Changed Country Music": http://www.wideopencountry.com/6-african-american-country-singers/

Sphinx Organization: http://www.sphinxmusic.org/

COPYRIGHT © 2017 VINCENT L. STEPHENS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.