Risks, departures, and pivots: When musicians change directions

One of the most stunning aspects of Summer of Soul, a 2021 documentary chronicling the long-forgotten performances from Harlem’s Cultural Festival staged in the summer of 1969, directed by drummer Questlove, is its shear variety. The audience is treated to a spectrum of black music including gospel performances from Mahalia Jackson, the Edwin Hawkins Singers, and The Staple Singers, funk from Sly and the Family Stone, electric blues from B.B. King, Afro-Latino music from Ray Barretto and his band, and Motown pop from Stevie Wonder, Gladys Knight & the Pips, and David Ruffin, among others. The final act introduced is the incomparable “High Priestess of Soul” Nina Simone whose music has always been unclassifiable and who delivers a command performance befitting her diva status.

Watching the audience’s rapturous response to the performers one is taken by their embrace of so many different styles. Unbound by genre and marketing categories the audience defies any stereotyping of black audiences’ musical tastes as a monolith. In this respect the most surprising response is their enthusiastic embrace of the 5th Dimension who deliver energetic, pitch perfect performances of “Don'tcha Hear Me Callin' to Ya” and their epic hit “Aquarius/Let the sunshine In (The Flesh Failures).” Though perceived as a “pop” group because of their smooth sound hearing singers Billy Davis Jr. and Marilyn McCoo comment in the film on how welcomed the audience made them feel and how they defied stereotypes of black pop during the era, drew my attention to artists who have pushed the boundaries of genre.

Numerous popular artists have stepped out of the commercial straitjacket assigned to them by record labels and radio and followed their bliss. Below, I highlight several key artists and the albums that helped them defy the commercial norms of their era and produce notable works. Not every album is a classic artistically but each one represents an attempt to try something new.

Changing cultural scripts

Ray Charles: Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music Volume (1962; ABC Records)

The Florida born Ray Charles grew up exposed to many types of music including gospel, jazz, and country. After establishing himself as one of the pioneers of soul music in the late 1950s Charles took a seemingly 360 turn by recording an album of classic and contemporary country hits associated with Eddy Arnold, Don Gibson, The Everly Brothers, and Hank Williams, among others. Though this seemed as far removed from his soul, jazz, and blues roots he proved how versatile great songs could be. Whereas he recorded classic versions of Cundy Walker’s “You Don’t Know Me” and Don Gibson’s “I Can’t Stop Loving You” in a lush countrypolitan style elsewhere he took greater risks. He reinvents “Bye Bye Love” and “Hey Good Lookin’” as swinging brassy big band tunes, and recasts “Just a Little Lovin’ (Will Go a Long Way)” from a laidback ditty associated with Eddy Arnold to a horn-spiked shuffle with a strong backbeat. Though industry people had their doubts about this radical departure “I Can’t” hit #1 on the pop, R &B, and easy listening chart, “You Don’t Know Me” placed in the top 5 on all three charts, the album hit #1 (14 weeks!) on the pop chart and he won a Grammy. More importantly, his success expanded perceptions of what country music was and who could perform it successfully for generations. Charles followed it up with the 1962’s highly successful Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music Volume 2 and 1965’s Together Again.

Dylan goes electric...then country…then Christian?

Bob Dylan: Bringing it All Back Home (1965; Columbia); Nashville Skyline (1969; Columbia); Slow Train Coming (1979; Columbia)

After establishing himself as a promising voice in topical folk music Dylan shifted from his emerging identity as the Pete Seeger of his generation to a rocker, a move signified by his use of electric guitar on most songs on Bringing it All Back Home a classic notable for “Subterranean Homesick Blues” and “Mr. Tambourine Man” among others. At the time his audience was folk-oriented was very self-serious and viewed itself as pure, intellectual, and anti-commercial thus the mass booing of Dylan’s electric “rock” performance at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival. Undeterred, Dylan emerged as an impish entertainer and chameleon rather than a strictly political role model which opened up his music and persona.

Eternally curious—and unpredictable—Dylan integrated aspects of country music on Nashville Skyline. In addition to embracing more straightforward lyrics and structures, in the country tradition, he adapted a creamy crooner style quite different form his nasally snarl. The album yielded several classics including “Lay Lady Lay” and “Girl from the North Country” sung with Johnny Cash.

Though he spent most of the 1970s inhabiting the singing style and vocal approach he was famous for he stunned many with 1979’s Slow Train Coming which followed his conversion to Christianity. Whereas the influence of traditional U.S. forms such as country, folk, and blues were evident in earlier stylistic experiments this fused rock music with Christian themes rather than playing like a traditional gospel record. Dylan maintained this approach on 1980’s Saved and 1981’s Shot of Love before returning to secular music on 1983’s Infidels.

Modernization

Barbra Streisand: Stoney End (1971; Columbia)

After nearly a decade of remarkable acclaim and commercial success on Broadway, film, television, and recordings, America’s most successful singing actress hit a generation gap at the end of the 1960s. Whereas her peers were singing about opposition to war, the pleasures of recreational drugs, and free love, Streisand was singing showtunes associated with previous generations. Though always more an albums artist than a hit machine her sales waned at the end of the 1960s. Aware of her dated image and on the advice of her record label she shifted from recording a concept album of Alan and Marilyn Bergman songs called The Singer to recording tunes from newer songwriters including Laura Nyro, Joni Mitchell, Harry Nilsson, and Randy Newman. Despite her own misgivings about singing contemporary singer-songwriter music the Nyro’s title track became a hit and Streisand was suddenly making records with a rock rhythm section rather than in front of an epic orchestra. Encouraged by its sales she continued exploring more contemporary songs by Nyro, John Lennon and Carole King on 1971’s Barbra Joan Streisand. For the rest of the 1970s Streisand redefined her image as a contemporary singer covering Paul Simon and Stevie Wonder and even recording disco tunes like “The Main Event” and her epic duet with Donna Summer “No More Tears (Enough is Enough).”

“Little Stevie Wonder” grows up and so does black pop music

Stevie Wonder: Music of my Mind (1971; Motown)

“Little Stevie Wonder’s” stunning live hit “Fingertips” gave him his first #1 hit in 1963 and made him a cultural phenomenon at the age of 13. For the next decade he emerged as a remarkable multi-instrumentalist, creative interpreter and gifted songwriter. As a Motown artist, however, he was expected to conform to its assembly line approach to conquering the youth market through hit singles. In 1971 Wonder, then 21, challenged the Motown ethos by demanding artistic control as a condition for of renewing his contract. Motown knew he was a highly desirable artist with options at other record labels and conceded to his demands. The result of the new Stevie Wonder was his first album masterpiece Music of my Mind. Though it didn’t spawn big radio hits (though “Superwoman” and “I Love Every Little Thing About you” are classics) it gave Wonder room to display the scope of his talents from songwriting, to production, to his mastery of synthesizers.

The album’s focus on songs over singles ushered in a new era in black popular music toward a focus on producing great full-length albums, often conceptual in nature. Wonder’s success inspired Marvin Gaye whose What’s Going On also found him breaking away from the commercial instincts of Motown toward a more thematic, conceptual approach to music making. Wonder’s remaining 1970s albums Talking Book (1972), Innervisions (1973), Fulfillingness’s First Finale (1974), and Songs in the Key of Life (1976), constitute the most ambitious and accomplished suite of albums released by a popular artist of that decade. It all began with Music of my Mind.

Expanding the boundaries of “country

Willie Nelson: Stardust (1978; Columbia Records)

After working as a fledgling singer-songwriter Nelson garnered a higher profile when singers like Patsy Cline started covering his songs. By the 1970s he was a major figure in country music with hits like “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain” and was a prominent face of “Outlaw” country. Suddenly in 1978 he, with the production assistance of Booker T. Jones, released Stardust an album of standards including “Georgia on my Mind” and “Someone to Watch Over Me.” Rather than hiring on orchestra or radically deconstructing the songs he interpreted them in a straight-ahead acoustic setting that allowed their melodic grace and lyrical subtlety to soar. Despite ongoing anxieties in country music about “authenticity” his ability to interpret the song sin his own style made them a natural extension of his unique style. The set topped the country albums chart, where it remained for charted for a decade, crossed over to the pop chart, and became a multi-platinum seller. Nelson became a reliable interpreter of standards continuing this approach on 1981’s Somewhere Over the Rainbow, 1983’s Without a Song, 1988’s What a Wonderful World, 1994’s Moonlight Becomes You, 2009’s American Classic, 2013’s Let’s Face the Music and Dance, 2016’s Summertime: Willie Nelson Sings Gershwin, 2018’s My Way, and 2021’s That’s Life.

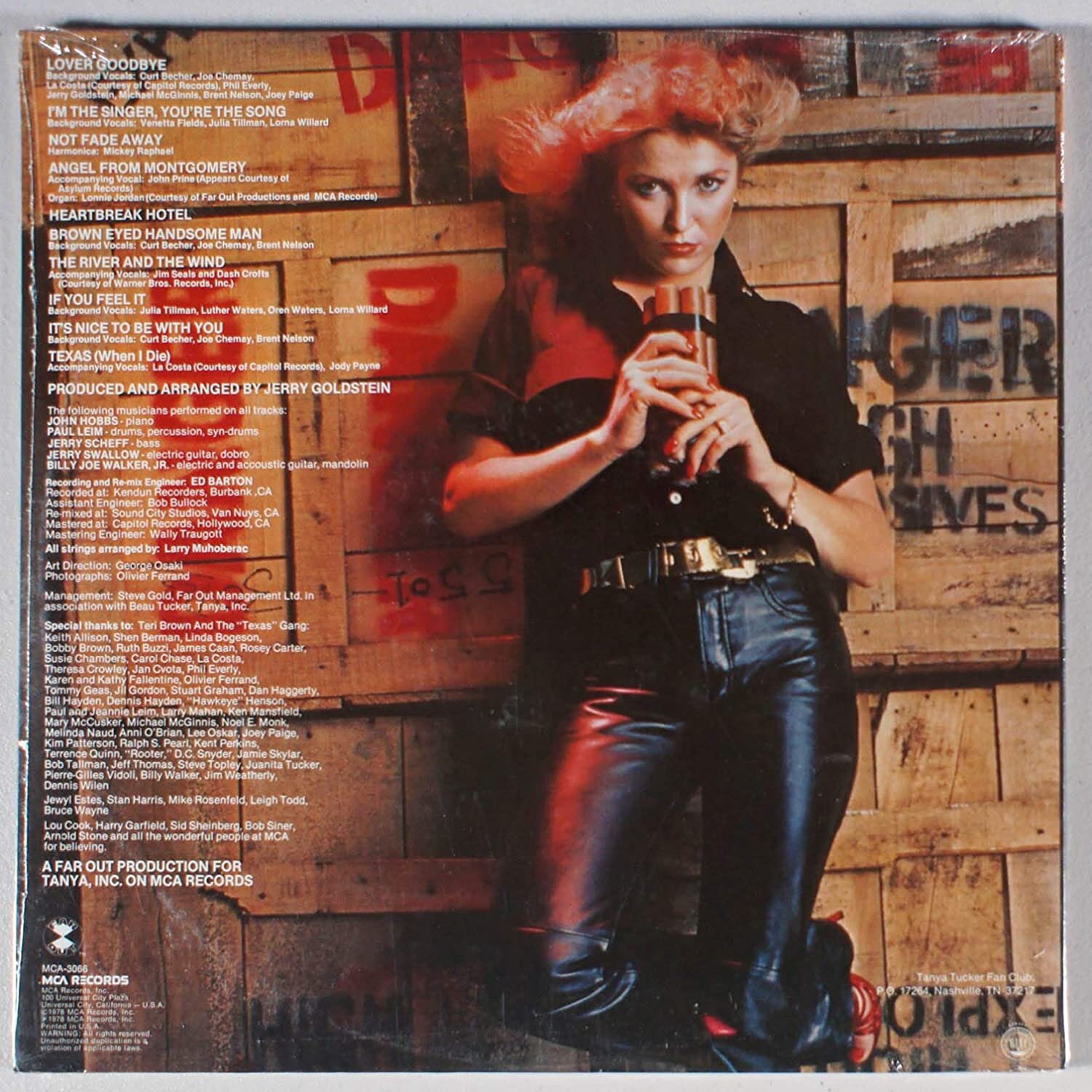

Tanya Tucker: TNT (1978; MCA Records)

Just as albums regarded as “classic” can fail to age well and defy their reputation, albums viewed as “notorious” or “controversial” can warrant a second chance. Country legend Tanya Tucker’s alleged pop crossover set TNT exemplifies this issue. After six years of recording Southern Gothic songs Tucker, who had turned 18 recently, wanted a change. She switched to manager Jerry Goldstein, moved to California, and sought out a newer, sexier, younger sound and image. Though many people dropped their jaws at the cover image of a leather clad Tucker holding a microphone in her hand unsubtly snaked between her legs, as well as the back cover where she leers at the camera in a red leather jumpsuit holding a stick of dynamic, the music was mostly good. The new tunes ranged from the growling “Lover Goodbye” to the sappy original “I’m the Singer You’re the Song” are somewhat dated. More promising was its one hit “Texas (When I Die)” (#5 country charts) a rollicking country-rock singalong tune well-suited to her persona. The essence of the album, however, was the finest rendition yet of John Prine’s “Angel from Montgomery” and superlative covers of the rock n’ ‘roll classics “Not Fade Away,” “Brown Eyed Handsome Man,” and “Heartbreak Hotel.” These are great songs interpreted with brains and gusto. Had she made a full-fledged rock ‘n’ roll cover album (as John Lennon did on 1975’s Rock and Roll) instead of blending rock with country-MOR mush she could’ve legitimately repositioned herself as a full-time rocker. She nearly did on 1979’s Tear Me Apart a rock set produced by Australian glam rock producer Mike Chapman. Alas, it had no hits and she floundered at Arista Records before returning to more palatable country hit material on 1986’s Girls Like Me. Had the country audience been more open Tucker might have blazed an innovative rock flavored approach to country, one that other country artists, like Dwight Yoakam and Garth Brooks, have embraced openly since then.

Inspirations from the past

Linda Ronstadt: What’s New (1983; Asylum); Canciones de Mi Padre (1987; Elektra/Asylum)

From 1974’s Heart Like a Wheel to 1982’s Get Closer Linda Ronstadt was the most popular all-around female singer in pop music. Then in 1980 she decided to perform in a production of The Pirates of Penzance at New York’s Public Theater which had an acclaimed run on Broadway from 1981-82. Her confidence singing Gilbert and Sullivan’s demanding operetta, the changing musical landscape (MTV debuted in 1981), flagging sales (Get Closer on went gold), and a desire for something new. The result was 1983’s What’s New a lush orchestral standards album of torch songs arranged by Nelson Riddle who was famous for his work with Nat King Cole, Ella Fitzgerald, Judy Garland, and Frank Sinatra. Though the album is uneven in execution it was mostly acclaimed at the time and became a surprising hit reaching #3 on the album chart, earning her a fifth nomination for the Female Pop vocal Performance Grammy, and selling over 3 million copies. Smitten with the experience she recorded 1984’s Lush Life and 1986’s For Sentimental Reasons which were also hits.

If her audience found her shift from country-rock and pop to pre-rock popular songs abrupt she really threw folks for a curve on 1987’s Canciones de mi Padre. Having defied all logical odds with the sales of her standards albums her record company reluctantly allowed her to record an album in Spanish steeped in the mariachi music tradition. Though Ronstadt’s father was Mexican and she grew up singing Mexican folk songs, she was perceived as “white” and few knew that Lola Beltrán was one of her idols. Ronstadt worked with Mexican violinist and composer Ruben Fuentes on this sparkling set of rancheras and huapangos. In the context of Fuentes’s stirring arrangement Ronstadt’s voice has never sounded as full or expressive. Though it only rose to #42 on the pop album chart it has sold 2.5 million copies making it the biggest selling non-English album in U.S. pop music. The response was so strong she hosted the musical special Canciones de mi Padre through PBS’s Great Performances series and won a Primetime Emmy for her impassioned vocal performances (Watch the video below).

In addition to earning Ronstadt a Grammy in the Best Mexican/Mexican American Album category it spawned the 1992 sequel Mas Canciones which earned her a second Grammy in this category. In 1992 she also released an album focused on Afro-Latin music titled Frenesi. In 2021 Canciones de Mi Padre was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame.

“Country” gets “real”

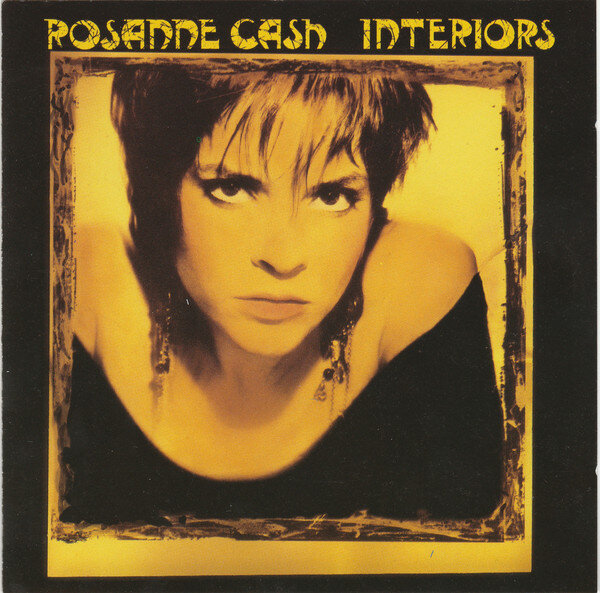

Rosanne Cash (1990; Interiors)

Despite the stereotype of country music as the most accurate cultural representation of white working-class emotions and “authenticity” country music is as slick and commercial as any popular genre. Rosanne Cash gained commercial success and critical respect throughout the 1980s thanks to smart, perceptive original songs like “Seven Year Ache” and inspired covers like her version of The Beatles’s “I Don’t Want to Spoil the Party.” Though she was always more sophisticated and adult than the slick country divas and hat acts that dominated 1980s country she turned her back on country commercialism on 1990’s Interiors. Combining the plaintive honesty of folk with directness of rock she alluded to her struggling marriage to Rodney Crowell as a vehicle for probing the cultural myths about love, family, and country that country music and Americana music romanticized. The result is an unusually spare, honest, and searing portrait of what it means to own your own truth. For Cash there was no turning back, and she has spent the last 31 years creating some of the finest music in contemporary folk music.

Redefining “jazz” one song at a time

Cassandra Wilson: Blue Light Til Dawn (1993; Blue Note)

Cassandra Wilson began her performing and recording career as a vocalist in alto saxophonist Steve Coleman’s experimental group M-Base an acronym for “macro-basic array of structured extemporization.” Though she debuted as a leader 1986’s Days Aweigh, her third album 1988’s Blue Skies, a bop inspired collection of standards, garnered her widespread acclaim. Disinterested in repeating herself she continued mixing original material sprinkled with the occasional standard in unorthodox arrangements. On her debut album for Blue Note she synthesized her experiences on what was a radical repertoire of songs for a vocal jazz album that included Robert Johnson, Joni Mitchell, Anne Peebles and Van Morrison, as well as originals. Beyond the songs themselves was Wilson and producer Craig Street’s radical recasting of songs in sparse, blues-inflected arrangements, with touches of African percussion and jazz improvisation. Her acclaimed 1995 set New Moon Daughter furthered this direction, including songs associated with Hank Williams, U2 and The Monkees.

Collectively, these albums pushed contemporary vocal jazz into more adventurous territory. Instead of rehashing standard songs in formulaic arrangements progressive jazz-based interpreters are expanding the form. Since the 1990s jazz has seen songbooks dedicated to the songs of Kate Bush (Theo Bleckmann), Stevie Wonder (Nnenna Freelon), Randy Newman (Roseanna Vitro), Tom Waits (Holly Cole), Sting & the Police (The Tierney Sutton Band), and Laura Nyro (Billy Childs featuring various artists), among others. Numerous artists, such as Gretchen Parlato, Ian Shaw, Curtis Stigers, and Cyrille Aimee also regularly incorporate contemporary songs on their albums. By expanding the canon and adapting arrangements to the unique contours of these songs newer voices in jazz have deepened its relevance.

COPYRIGHT © 2021 VINCENT L. STEPHENS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED