Learning to Listen Excerpt 14: Linda Ronstadt: Wandering and wondering through pop

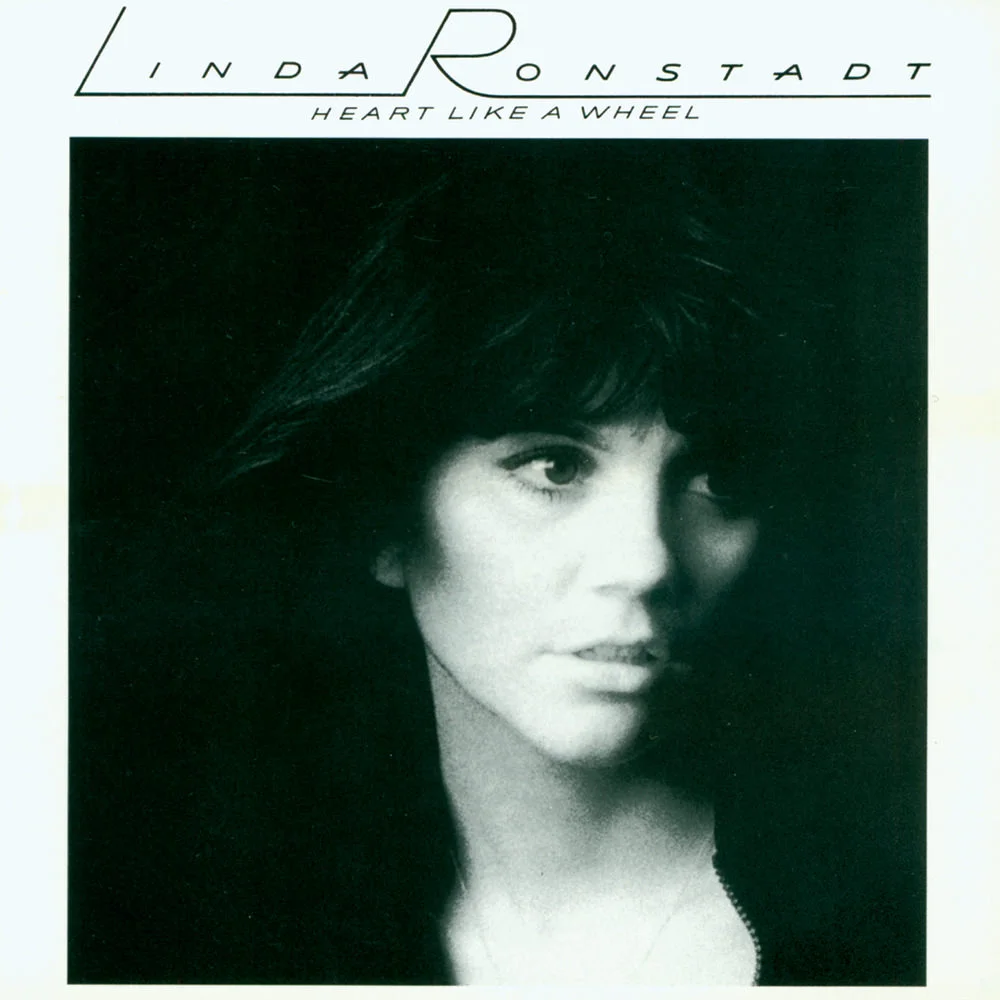

When writing about Linda Ronstadt (b. 1946) the temptation is to focus on her most commercial period (1974-80) when she was a major album seller and a regular presence on the radio via her eclectic genre spanning style. Interestingly she has openly disavowed many of her recordings from this era. While I would not disavow them so hastily—Heart Like a Wheel and Simple Dreams are pioneering efforts in many respects—I agree with her that her singing reached a peak of refinement and control well after her most commercially fertile period. Further, for all of her renowned stylistic eclecticism she actually projects a very consistent persona across genres.

Ronstadt was certainly among an elite commercial vanguard of popular singers of the mid-to-late 70s when she released a series of highly influential albums. Most of them went platinum and multi-platinum, including three that topped the albums chart: 1974’s Heart Like a Wheel, 1977’s Simple Dreams, and 1978’s Living in the U.S.A. Industry figures in mainstream pop/rock and country music also recognized her gifts; in addition to receiving industry accolades—including country and pop vocal performance Grammies—she became a heavily sought after duet partner and harmonizer for other vocalists (e.g. Karla Bonoff, Emmylou Harris, Little Feat, Nicolette Larson, Wendy Waldman, Neil Young).

This level of popularity was rare for female solo singers at the time, but her importance extends beyond sales data and pervasiveness. Ronstadt and her producer Peter Asher and frequent arranger Andrew Gold crafted a uniquely eclectic sound. This style is commonly referred to as “country rock,” but is better understood as a rock fueled approach to arranging and producing that yielded a range of performances, particularly interpretations of ‘50s and ‘60s rock ‘n’ roll/rock and R&B, vintage country and folk tunes, and ‘70s folk-pop, in a polished, layered style. As her primary musical arranger Gold figured out how to craft a thrilling interplay between guitars, keyboards, and drums in a manner that captured the mood/tone of Ronstadt’s material and configured the lead voice and background vocals as essential components. Some critics have viewed this style as slick, formulaic and cookie cutter, but others heard it as a meticulous, intricate approach that imbued her records with consistency and stylistic integrity.

Regardless the imprint of her 1974-78 albums—Heart Like a Wheel, Prisoner in Disguise, Hasten Down the Wind, Simple Dreams, and Living in the U.S.A—can be heard in a wide range of vocalists during the era. Melissa Manchester, Bonnie Raitt, Rosanne Cash, Jennifer Warnes, as well as Larson, Waldman, and Bonoff were influenced by her sound. There are also younger generations of female country singers, such as Reba McEntire, Wynonna Judd, Matraca Berg, Trisha Yearwood, Leann Rimes, and Martina McBride who borrow liberally from Ronstadt’s full-throated vocal throb…

Ronstadt expanded her vocal palette in 1980 when she portrayed Mimi in the New York Public Theater’s production of The Pirates of Penzance, which became a feature length film in 1983. But as a recording artist her eclectic reputation emerged when she recorded three albums of pre-rock material (i.e. Ira & George Gershwin, Billy Strayhorn, Duke Ellington, Rodgers & Hart songs) arranged by the eminent Nelson Riddle most famous for arranging recordings for Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole, Judy Garland, and Ella Fitzgerald. What’s New, Lush Life, and For Sentimental Reasons are her most divisive recordings, though she has cited them as her favorite recordings. This is important for understanding her disdain for her initial successes and enthusiasm about her post-1980s work...

Her shift away from the attitude and punch of rock and R&B is important because this signified the aspirational aspect that pervades her singing. There has always been a bel canto aspect to her singing—a purity of tone, a directness in her pitch, and a love of sound and texture that the standards albums drew out of her. Though I agree with her detractors that her vocal performances of pre-rock material are often stiff and meandering, I believe her singing actually improved after she recorded these three albums. Her singing became richer; her vocal tone grew fuller, and she delved into the nuances of lyrics with a newfound intimacy.

If Broadway and pre-rock pop standards are not her ideal métier she certainly grasps the vernacular of country, folk, and rock genres. Ronstadt followed up the standards trio with another Trio—a collaboration with Emmylou Harris and Dolly Parton in which they harmonize on a series of classic country and folk tunes and a few new songs written by Parton, and Linda Thompson. Her performances are lovely and restrained, but the more telling showcases of her newfound growth are 1987’s Canciones de mi Padre and 1989’s Cry Like a Rainstorm, Howl like the Wind.

Ronstadt’s father was part Mexican and his heritage informed her and her siblings’ childhoods. She has spoken lovingly about the iconic Mexican ranchera singer Lola Beltran being her primary idol as a singer and the inspiration shines through on Canciones. On the album she sings a range of classic Mexican folk songs—particularly rancheras (rural farm songs) and huapongos (love songs) — in polished acoustic traditional settings. Her singing showcases a wider range to her singing than ever—notably the falsetto flourishes and vocal cracks characteristic of Mexican folk singing—and her technical skill—pitch, purity, control—is matched by a higher level of emotional abandon than she’s ever exhibited. A sense of joy and relief emerges throughout particularly on the dynamic vocals on “La Cigarra” (“The Cicada”) and “La Charreada.” Some have accused her of making these songs “slick” or approaching them too reverentially, but to my ears she is more credible as an ambassador of this music for a mainstream pop audience than she was for Gershwin, Rodgers & Hart, and Strayhorn

Whereas she was a self-conscious visitor in that milieu—no definitive performances emerged from her Riddle sessions—she sounds emotionally and physically connected to her material. The PBS TV special (Canciones de mi Padre: A Romantic Evening in Old Mexico) and interviews she conducted in relation to this album—which was commercially riskier than her standards excursions—indicate the full-scale passion she brought to this project. Unsurprisingly she revisited this genre on 1991’s Mas Canciones and expanded her interests to Afro-Cuban and salsa music on 1992’s Frenesi. She has not displaced Beltran as the premiere female interpreter of Mexican folk music, but her performances are potent, and certainly a respectable introduction to the genre….

On her ‘70s pop records she often imposes her potent belting style on material that warrants a simpler approach. On Cry her penchant for full throated belting suits the epic emotionalism of what she’s singing. This is especially true on the downbeat Jimmy Webb ballads “Still within the Sound of My Voice,” “Adios,” “I Keep it Hid” and “Shattered”—whose titles indicate the emotional heft and regretful sentiments these songs express. Webb’s expansive melodies provide breathing room for her emotive belting style. She is certainly no slouch on her ‘70s recordings, but there is sometimes a wan tremulous quality to her earliest singing that feels unctuous; she can easily run the lovelorn lass persona into the ground. However, her singing on Cry is poised and emotive—a large scale embodiment of emotion surrounded by meticulous arrangements: keyboards, strings, drums, guitars, and on some cuts a vocal choir, yet it always feels intimate and conversational, rather than feeling like she is broadcasting her emotions to whomever will listen. Her classy duets with the wonderful tenor Aaron Neville also draw out unique elements of her persona and ultimately her voice in a manner no other partners have achieved. They’re playfully devoted on “I Need You,” profoundly tender on “All My Life” and “Don’t Know Much,” and intensely soulful on their uniquely synchronous version of “When Something is wrong with My Baby.” Neville’s gentle style cajoles a vulnerability and radiant sexiness out of Ronstadt. On more up-tempo material like the R&B flavored “So Right, So Wrong” and Karla Bonoff’s rocking “Trouble Again” there is a gleeful, youthful charge to her singing; there’s a tongue-in-cheek, starry-eyed quality to her performances; she sounds renewed.

Her follow-up English language pop set, 1993’s Winter Light, features many of my favorite Ronstadt performances. Her most stirring performance is of The McGarrigle Sisters’ lilting “Heartbeats Accelerating.” After years of singing about the search for love she finds the perfect lyric: “Love, Love/ Where can you be/Are you out there looking for me?” which allows her to succinctly expresses a palpable ache with more directness than ever. Her vocal takes on Bacharach-David’s “Anyone Who Had a Heart” and “I Just Don’t Know What to do With Myself” borrow various cues from Dusty Springfield and Dionne Warwick, but she is so unbridled that the studied nature of these performances is moot. Both recordings build to well-earned climaxes and she sings them with such explosive force it’s actually a relief that the sound gradually fades toward the ending—there’s a vocal sweep not even her beloved models reached in terms of sheer intensity and power. Elsewhere she dons doo-wop apparel on the late ‘40s chestnut “It’s Too Soon to Know” and works up deliciously melodramatic ache on the 1964 Maxine Brown hit “Oh No Not My Baby”….

Winter Light was critically well-received, but it signified a shift toward what was interpreted as an adult contemporary/soft rock style in the late 80s/early 90s. “Soft Rock” usually signifies biteless music—romantic ballads with clichéd lyrics, predictable rhythms, and sleek production values—whose glossy predictability parallels middle-aged settlement. Sapped of R&B gospel roots and rock’s energetic vitality soft rock is easily dismissed as music of defeat and surrender. But listening closely to her ‘90s music you hear some of her most buoyant and soulful singing…

By the early 1990s her distance from the spotlight seems to have allowed her, an apparently very reserved and private person, to record with greater emotional intimacy. Winter Light features two of her most personal recordings. On Emmylou Harris’s lamentative waltz “A River for Him” she dedicates the song to “Baby Jessica” who was embroiled in a highly publicized, tumultuous adoption case. Around this time Ronstadt quietly became the guardian of two children herself. She also responded to anti-immigration sentiments recording Tish Honojosa’s “Adonde Voy (Where I Go)” a narrative folk ballad. Whereas she previously isolated her Spanish-language recordings (except 1976’s self-penned “Lo Siento Mi Vida”) there is a sense that she is fully integrating multiple aspects of her identity. While I would not posit her prior recordings as inherently less personal or autobiographical, the greater sense of emotional openness she consciously presents on Winter Light is notable…

About half the tracks featured on 1995’s Feels Like Home were originally intended for Trio II (eventually released in 1998), but because of scheduling conflicts Dolly Parton was unable to complete the tracks with Harris and Ronstadt. Ronstadt had Parton’s vocal harmonies erased from a few tracks and replaced her with other background vocalists (including popular singer Valerie Carter and bluegrass singer Claire Lynch), and then recorded a number of songs as a soloist including Tom Petty’s “The Waiting,” Matraca Berg’s “Walk On,” “Women Cross the River,” “Teardrops Will Fall,” and “Morning Blues.” The result is a thoroughly engaging album that reminded many reviewers of her ‘70s records though it arguably embodies the notion of “country rock” more faithfully than any of her ‘70s albums. When one considers the country and R&B elements the Flying Burrito Brothers and Gram Parsons pioneered, Ronstadt’s eclectic approach is a genuinely modern representation of the style…

After recasting pop/rock oldies as lullabies on Dedicated to the One I Love she explored a range of rock and R&B songs on 1998’s We Ran. Here she makes her most rock-oriented album ever. She soars on John Hiatt’s epic title track, reaches for quiet intimacy on Bruce Springsteen’s “If I Fall Behind,” and asserts her abilities as an R&B stylist on the sultry “Ruler of My Heart” (originally recorded by New Orleans soul queen Irma Thomas) and the moody “Cry Til’ My Tears Run Dry.” She also evokes New Orleans on the sly shuffle “Give Me a Reason,” and leans in a country-soul direction on “Damage.” This album is in many ways a bridge to its predecessor in demonstrating her ability to re-inhabit and redefine the terrain she pioneered but with greater confidence and control than her initial commercial albums….

Though none of her later albums has impacted the pop landscape with the reach of Heart Like a Wheel, not possible at this point, they are aesthetic achievements of comparable accomplishment. Listeners who may have assumed she had slipped into soft rock territory and was abandoning her past would hear a level of passion comparable to her career defining records. They would also hear a sense of balance and control befitting a singer with her varied experience as an interpreter and her emotional maturation as a human being. Her stylistic adventures have culminated in a keener sense of how to illuminate her material rather than merely showcasing vocal textures. She has finally reached a point of reconciling her desire to achieve bel canto vocal perfection with the actual demands of her material and the result is that her post-1987 performances are arguably her most consistent and convincing.

The aspirational perspective she adapted during the early 1980s experiments with operetta and pop standards seems to have morphed into a refreshed attitude toward her métier of country, folk, and popular material. She seems to have developed a more organic sense of what constitutes a quality song and the kinds of tools she needed to interpret her material more vividly. Her move toward more “prestigious” songs and “sophisticated” settings seem to have clarified something in her and have made it easier to access her own voice as an interpreter. By voice I refer to her literal voice and a fuller, more coherent vision of the recording landscape including every aspect from songs to arrangements to players. It’s notable that she is credited as producing and mixing Winter Light and Feels Like Home—two of her finest recordings—alongside George Massenburg, and mixing Trio II with him.…

During the 2000s she also explored Cajun music on the collection Evangeline, returned to standard material on the small group set Hummin’ to Myself, and in a collaboration with Cajun folk artist Ann Savoy (of the Savoy-Doucet band) she recorded an album of Cajun songs, chansons, and a few pop tunes in an acoustic Cajun-flavored setting on Adieu False Heart….

Hummin’ was recorded for the jazz-associated label Verve Records. By the early 2000s baby boomers were virtual ghosts at pop radio and depended more on album sales. A number of labels like Blue Note and Verve added adult pop/rock/R&B acts to their roster, alongside their usual stable of jazz acts. Incidentally, Hummin’ was released only two years after Rod Stewart revived his commercial fortunes with what was the beginning of five volumes of his takes on pre-rock popular songs. It’s not clear how influential Stewart’s success was on Ronstadt—who had performed the same feat 20 years earlier—but what is telling is her choice to record obscurities like the title track and “Tell Him I Said Hello.” A full album of chestnuts would have been a far more commercial prospect. Similarly, the decision to record her voice in the intimacy of a jazz rhythm section rather than an orchestra suggested not only a turn away from commercial predictability but a desire to expose her voice, phrasing and lyrical skills in a more vulnerable setting.

Full time jazz-oriented and cabaret singers routinely do this of course, but Ronstadt’s venture is a significant turnaround in her sense of confidence. Apparently prior to recording the Riddle albums (~1982) she had recorded a few standards with producer Jerry Wexler with spare piano accompaniment, but was dissatisfied and it was never released (you can listen to it on You Tube). 14 years of recording had not yet prepared Ronstadt for the intimacy of the Wexler sessions but in the 22 years since she developed a stronger sense of security in her talents. Though Hummin’ has some weak moments (for example she belts during various phrases in “Tell Him” and “I’ll Be Seeing You” when it would be more effective to croon) she remains a steadfastly earnest romantic who exhibits visceral yet still measured passion. But her playful approach to the lightly swinging “Get out of Town,” and bittersweet humor she employs on the title track and “Never Will I Marry” show notable growth in her rhythmic instincts and a tighter connection with the tone of song lyrics. She no longer sounds intimidated; rather she sounds like a singer seeking a unique and original interpretation—and sings with guts.

Her last album before retiring in 2009 is 2006’s Cajun themed Adieu False Heart, a fine mixture of old and new ideas from Ronstadt. Songwise there are selections from respected contemporary country/folk writers like Julie Miller and Richard Thompson, a country classic by Bill Monroe, the pop/rock oldie “Walk Away Renee” and a host of songs by lesser known writers. She and Cajun music expert Savoy (they jokingly call themselves The Zozo Sisters) have a lovely harmonic blend. Savoy takes the lead on the two French songs “Plues Tu Tournes” and “Parlez-Moi D’amour.” Ronstadt sings in French and English, adding to her stylistic versatility and making her a kind of vocal polyglot. On her solo selections there are many treasures: most notably a very intimate, haunted version of “King of Bohemia”—patient, clear, and spacious. Since retiring quietly from recording Ronstadt she has received multiple honors for her contributions to American and Latin-American popular music, and released the autobiography Simple Dreams in 2013. In 2014 she was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

COPYRIGHT © 2016 VINCENT L. STEPHENS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.